What gets counted counts...

A short time after I came into post I requested the reading lists for all courses in the Graphic Design Programme at CCW. I had been reflecting on the ways that my reference base was very white, male, modern and Eurocentric. I was interested to understand what the general pattern was across the programme and the different references we were using to teach Graphic Design.

At my most optimistic, I hoped I might learn something new.

Sadly, the data produced some completely expected results*

Only 0.3% of authors were people of colour

Only 18% of authors waere women

Only 11% of books had been published since 2000

100% of the books could be classified as Anglo/Eurocentric

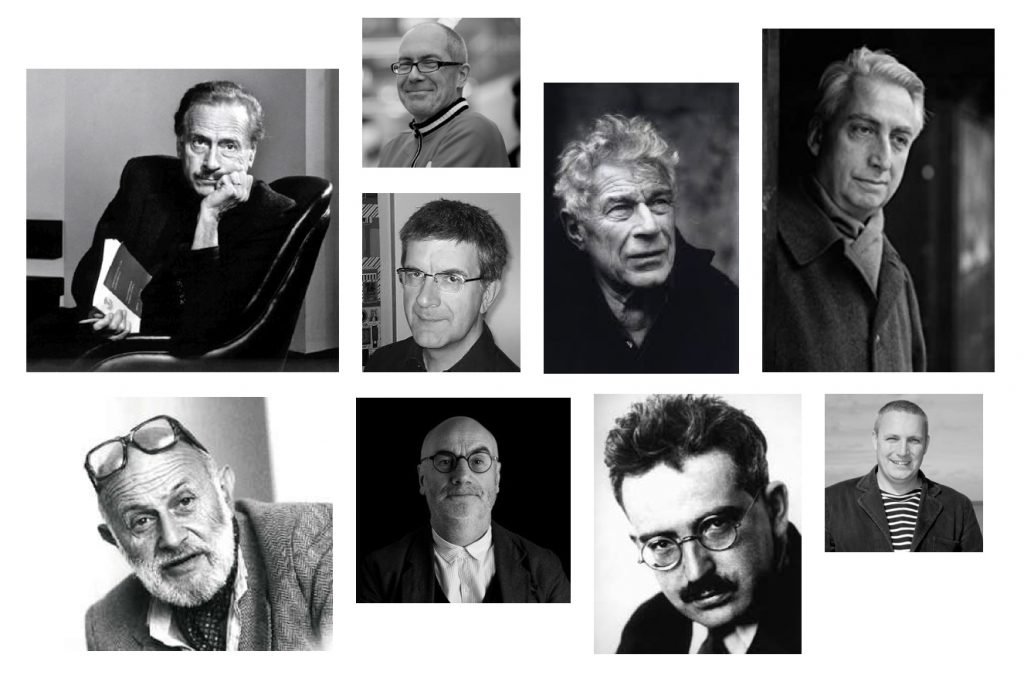

For the more visual among us, heres the most popular authors across the lists.

The great white sharks of Graphic Design.

These guys all had multiple books or appeared in multiple lists.

Lucky them eh?

This reading list is not the industry. But actually, it's not far off.

The lack of diversity in our reading lists is not an isolated issue; it reflects the larger problems of representation within the graphic design industry. The homogeneity of our reference materials mirrors the predominantly white and male composition of the field. According to the Design Council, 88% of design managers in the UK are white, and the workforce is 78% male, despite women making up 63% of all art and design students. Although women are entering the design industry at a faster rate than men (up 42% since 2010) they are less likely to be in senior roles than men.

We must also notice out the overwhelming whiteness of this picture. My longstanding feminist rage at representation in the discipline cannot not afford to be blind the witness of that same references base.

*It's important to say here that the reading lists alone were not enough to tell me this. I hand coded the missing categories. So, like any dataset, I am filtering reality in a highly subjective way. Biases addressed, the numbers are helpful in a way that they give us something to grasp at. A picture of some kind of 'reality' if you like.

What gets counted, counts

Much of the institutional effort around diversity and decolonization has centered on diversifying reading lists and re-contextualising collections. This is understandable and to a degree, helpful. When I think of it from a disciplinary perspective, I can see how reading lists and collections can be considered sites of social reproduction. If we assume this to be the case, I guess we can also assume that what's on them (reading lists) and in them (collections) maintains, secures and privileges certain ways of knowing, being and practicing graphic design. So, any process that exposes these privileges should, in theory, be a useful process. If only to provide us with a context on the discipline from which we might be able to expand our academic and creative practices a bit more consciously (Depatriarchising Design 2019).

That said, the classification system is really poorly designed. A classic top-down taxonomy. The sort of data you can extract from the Dewey Decimal System is really only useful for understanding who is writing about design. Unless the author is the designer, we can't actually glean much information about the designers that these collections represent. If we can't tell this, then we certainly can't learn anything about the ideas and practices that of these designers (Decolonising Design, 2016). We can take some educated guesses but to get closer, we'd have to go back to the beginning and start looking for information that has been left out.

Sound like a long process? Yea, it is. But it's happening. I've recently learned a bit about some of the institutional efforts to capture this missing data. Library Services staff are currently testing methods that might enable us to see some of the characteristics of UAL collections at scale. It all sounds (reasonably) exciting. However, it does rather make the institution the social actor in the process. The idea of the institution as both data collector and categorizer makes me itch. Probably because the acts of classification and categorization are just some of the ways that our grand Western epistemic totality has been. Many of these categories are based on (pre)existing social categories and binaries that we tend to reproduce without active reflection (Kvasny 2016).

It's not to say that there should be no categories, but I question who gets to define and decide those categories and how they are applied. Spolier; I don't think the institution is best placed for any of this work.

Figure/ground

Mostly I find myself thinking about the students role in all of this. When we frame this all as an institutional responsibility 'to provide’ for nonwhite others (Ahmed, 2012:45), are we not just reproducing whiteness as the norm? That students do not see their histories or identities reflected in the reading list should not detract from the fact they they don't see those things reflected in their course teaching teams or in the management of the institutions. Certainly not in positive or affirming ways.

The institutionalisation of diversity initiatives, such as diversifying reading lists and collections, can inadvertently create a figure/ground problem. In case you’re not familiar with this idea (it is like a second language for Graphic Designers), in Gestalt psychology, the figure/ground principle refers to the way our perception organises visual information into a prominent 'figure' that stands out from the less distinct 'ground' or background. When we bring representation to the forefront of decolonising work, we obscure the broader, systemic challenges that perpetuate inequality in design education and the industry. The 'figure' of diversified resources may be celebrated, while the 'ground' of underrepresentation in faculty, management, and the curriculum as a whole remains largely unaddressed. This selective attention can give the illusion of progress while allowing deeper structural issues to persist.

The other issues of framing diversity as something the institution must 'provide' is the way it inadvertently reinforces whiteness as the norm. I’ve sat in many revalidation panels as an internal reviewer where the discussion about the course reading lists ends can we get ‘more diversity.’ Sadly, this often results in random, uncontextualised references being wedged into a list of the usual suspects solely to tick the ‘representation’ box? It’s an entirely pointless move and it could in no way be described as truly ‘decolonising the curriculum.’ At it’s worst, it risks further marginalising the very students these initiatives aim to support. To decolonise and diversify design education, we have to critically examine the entire system, including our own biases and practices, rather than focusing solely on the more visible symptoms of the problem.

As academics, I think we all risk of mistaking decolonisation for more general inclusion work or worse, we see it as the work or somebody else. Very often, we place the burden of decolonising practice onto people who have been actively disadvantaged by it. While there are of course voices that must be centred in decolonising discussions, the responsibility for the work must be shared by all. It strikes me how often, students educate me on this. This year, for example, I've learned a lot by looking at what the students are referencing. It seems useful consider how their interests and reference bases could be used to inform our teaching. Perhaps because all anyone seems to talk about are reading lists and I feel like that conversation is a cul-de-sac. A reading list just seems like another way centre our own limitations and biases in the heart of the curriculum. Engaging students in the processes of both diversifying and decolonising the curriculum is crucial. For example;

Co-creating the lists: How might we involve students more meaningfully in the process of selecting and curating course materials? Can we put aside our own biases on what constitutes ‘knowledge’ and widen our minds to the ‘knowledges’ that reflect our students backgrounds, experiences, and interests? This would not only broaden the scope of the curriculum but also empower students to take an active role in shaping their education.

The Parallel Narratives project is a great example of this. An on-going undergraduate assignment co-developed by Natalia Ilyin and Elisabeth Patterson, it invites students to research and compile annotated bibliographies of 80-100 citations about a topic they believe did not gain entrance into the current, commonly-taught “canon” of design history.

Facilitating critical discussions: A symptom of our highly commoditised education system is our tendency to seek ‘feedback’ from students as though they were consumers. Course Committees and Student Satisfaction surveys are poor formats for a genuine sharing of experiences. It is important to reflect on how the actual opportunities we create to discuss issues of representation, privilege, and power dynamics in open and accountable ways. As educators, we are generally very poorly prepared to facilitate these sorts of conversations. There’s a wealth of work out there discussing the effective facilitation of ‘safe spaces,’ ‘brave spaces’ and now ‘accountable spaces.’ The language and the thinking moves far more quickly than the frankly glacial pace of change in our institutions. So, much of this starts to point to bigger question; to what extent is facilitation becoming a core skill for educators? How can institutions better support and enable educators in that?

Co-design of curriculum: My colleagues within and outside of education often ask me if I ‘miss designing.’ I find this question unfathomable. To me there is no more exciting design challenge than the design of education itself. I don’t believe I ‘stopped designing’ when I became an educator. However, that this question gets asked tells us a lot about how people view education. As a design educator I take every possible step to ensure that students understand and engage critically with their education as ‘designed.’ Every workshop, VLE instruction, learning outcome and interaction is designed. Sometimes well, sometimes poorly and sometimes, well, somewhere in the middle. As designers, I encourage students to consider this by making the assumptions underpinning the design of curriculum visible. This can help engage students and educators in an open discussion about educational design and help us all to see what is within our power to change. For me, this is the most effective and discpiline-appropriate way that I can encourage ‘feedback’ from students.

The Carrie Bradshaw Close

Looking at reading lists is a start… it got me here. However, diversifying and decolonizing design education requires a more holistic, critical, and collaborative approach. By engaging students in the process of shaping their learning experiences, we can create a more inclusive and equitable curriculum that reflects the diverse perspectives and experiences of our community. However, this work demands that we, as educators, confront our own biases, limitations, and assumptions about the design and delivery of education.

To truly transform design education, we must be willing to engage in open, accountable, and sometimes uncomfortable conversations about representation, privilege, and power. How might we develop ways for students to engage creatively and critically (Friere 1972) with both the issues and the process? As design educators, we can do this by recognising the inherently designed nature of curriculum and make visible the assumptions that underpin our educational practices. By doing so, we invite students to become active participants in the ongoing process of reimagining and redesigning education itself.

As we move forward, it is essential that we continue to question, challenge, and innovate in our approaches to diversifying and decolonizing design education. It’s journey not a destination – one that requires our collective commitment, creativity, and courage. By embracing this challenge, we have the opportunity to cultivate a new generation of designers who are equipped to create a more just, equitable, and inclusive world. We must question our urge to ‘act.’ In choosing to do this for students (rather than with them) we risk removing their agency to be part of the transformation.

So there's my thoughts for the day.

References

Ahmed, S, & Ahmed, A. (2012) On Being Included : Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Duke University Press

Alexander, Jacqui M. (2005). Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ansari, A & Martins, L & Oliveira, P & Keshavarz, M & Canli, E& Abdulla, D & Kiem, M & Schultz, T. (2016). The Decolonising Design Manifesto. Journal of Futures Studies. 23. 1

Butler, J (1993). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘‘Sex.’’ New York: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2004) Undoing gender New York: Routledge

Dyer, R (1997). White. London: Routledge.

Farnel, S. et al. (2018) ‘Rethinking representation: indigenous peoples and contexts at the University of Alberta Libraries’, The International Journal of Information, Diversity and Inclusion, 2(3), pp.2574–3430.

Frankenberg, R (1993). White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Friere, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York:Herder and Herder.

Hoechtl, N., Lozano, R., del Socorro Gutierrez- Magallanes, C., (2012) Decolonising the public university A collaborative and decolonising approach towards (un)teaching and (un)learning. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-‐40

Hooks, B (2010) Teaching, critical thinking: practical wisdom. London: Routledge

Kvasny, L (2006) Social Reproduction and its Applicability for Community Informatics

Jonsson, Fatima & Lundmark, Sofia. (2014). An Interaction Approach for Norm-Critical Design Analysis of Interface Design.

Maldono-Torres, N. (2007) ‘On the coloniality of being: contributions to the development of a concept’, Cultural Studies, 21(2/3), pp.240–270.

Mbembe, A.J. (2015) ‘Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive’, Forms the basis of a series of public lectures given at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER), University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, University of Cape Town and University of Stellenbosch.

O’Rourke, F. (2018) ‘Race, whiteness and the national curriculum in art: deconstructing racialized pedagogic legacies in postcolonial England’ in Kraehe, A.M., Gaztambide-Fernández, R. and B.S. Carpenter (eds.) The Palgrave handbook of race and the arts in education. Cham: Palgrave McMillan, pp.205–255.

Rosenblum, B. (2015) ‘Decolonizing libraries (extended abstract)’, Brian Rosenblum, 1 February. Available at: http://brianrosenblum.net/2015/02/01/decolonizing_libraries/ (Accessed: 8 March 2019).

Tuck, Eve & Yang, K.. (2012). Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization. 1.

Zabolotney, B. (2019) 'Locating new Knowledge in An Unacknowledged Discourse’, in Vaughan, L. (ed.) Practice Based Design Research. London: Bloomsbury, p24.