Pale, Male and Stale. Once again.

Explaining phenomena like racism and sexism—how they are reproduced, how they keep being reproduced—is not something we can do simply by learning a new language. It is not a difficulty that can be resolved by familiarity or repetition; in fact, familiarity and repetition are the source of difficulty; they are what need to be explained.

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life

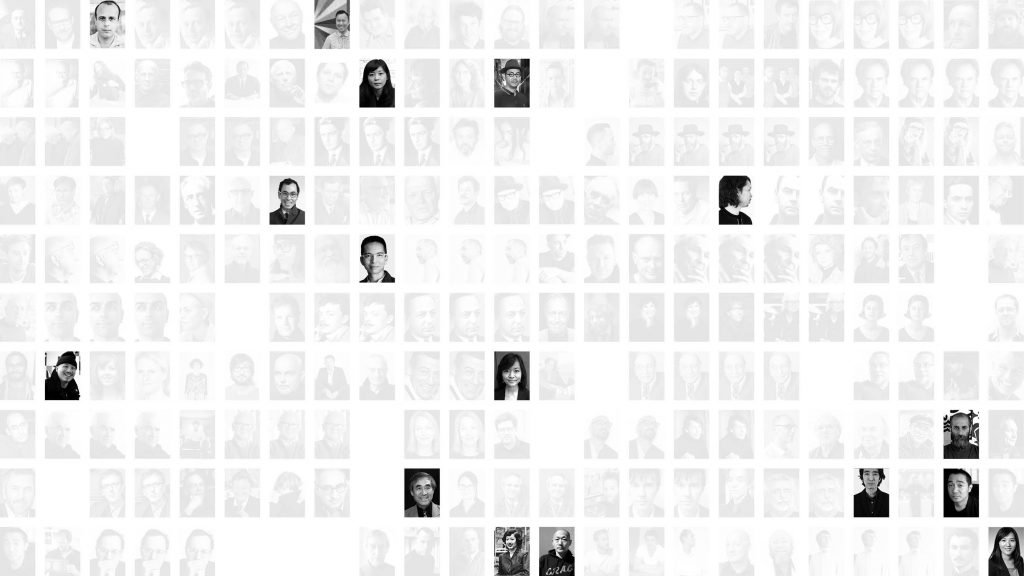

This is (most) of the designers featured in the physical books in section 741.6092 at Chelsea College of Arts. The section entitled ‘Graphic Designers.’ This data was gathered as part of a project called 741.6092 run on the Grad Dip Graphic Design at Chelsea this year.

If we imagine the library collection as a way to model the disciplinary world of graphic design, then considering what and who is represented in it will expose some of the assumptions and privileges that disciplinary thinking and education is based upon.

Who this is not

What is important to note about these images is that the pictures are not the authors of the books in the collection. They are of the designers featured in those books. We found we cared far less about who was writing about design as by who was doing the designing; their ideas and practices, their origins. So we, as tutor and students, gathered these layers of data often missing from the Library classification system. This enabled us to have a more nuanced conversation around the issues.

Disclaimer

This data represents a small percentage of the total graphic design collection at UAL. This is just the physical collection at Chelsea. However, this collection is the one most available to us at staff and students at Chelsea for reference and research on campus. It’s also important to say that some images of designers are missing. However, when I quote figures in this post, I am talking about the dataset overall.

What it shows us

We used a range of lenses to analyse our data and it told us a lot of stories. Many of these are documented in the workshop notes. I won’t cover them all here. I will mostly just address what these visualisations focus on.

What graphic designers ‘look like’

If you’ve practiced/studied/taught design in the UK, there are some entirely expected things about these images. The prevalence of white bald men (designers) gazing thoughtfully into the distance. The chunky-black-framed-glasses. I have no doubt if you zoomed out, you might find some striped t-shirts and some blue jackets. There’s nothing particularly confronting about this data until you start to filter it.

For example, let’s remove the male designers...

Things get a bit more sparse. More than they should given that 63% of all students studying creative arts and design courses at university are female (Design Council, 2020). Notice too how five of these designers have multiple books about them, which knock even more off the total number of female designers represented.

In fact, let’s do that…

Now let’s see what happens if we remove all the white female designers.

Two of the remaining designers here, Cara Ang and Michelle Tan, work for the same studio in Singapore (Asylum). Tomoko Miho, is sadly now dead. Yang Liu in the bottom right hand corner the only female Chinese designer in the collection. She is also the only Chinese designer in the collection, full stop.

And of course these binary definitions of gender mask other stories.

This is Kate Morross. The only designer in the collection (that we know of) who identifies as non-binary.

Designers of color

Let’s go back to our not-quite-full portrait of the collection.

Now let’s remove all the white designers. Male or female.

Let’s knock two off for Takahiro Kurashima, who is featured in three books.

Let’s also filter out the designers from Anglo/Euro regions.

What we have left in the actual data are 16 designers (we were unable to find an image of 3 of them). 12 of these designers are from Japan. Apparently, Asian designers are mostly Japanese.

This is the rest of the world

I think, as educators, we understand in theory that the diversity of our collections is not good enough. What this process highlighted for me and the students on the Grad Dip was just how badly we are doing.

As the UAL Collection and Development Policy notes, the goal here is to ‘develop inclusive and diverse collections, to foster a sense of belonging at UAL for all our library users.’ We can legitimately question how this collection is ‘fostering a sense of belonging’ for the students on the Grad Dip who are 90% female, 82% Asian (and 0% Japanese). We might also extend that questioning to any non-white student, and perhaps any female or non-binary student.

After doing this project, I’ve realised that I need to think a little harder about how we think about references at the disciplinary level; beyond the library and beyond it’s collection. Publishing in the traditional sense is not a model that lends itself to diversity. There are very real barriers to obtaining and purchasing certain types of books. Particularly books from outside the very Anglo/Eurocentric publishing world.

Same problem, different data

When I looked at the authors represented in the graphic design reading lists at CCW two years ago, I was interested in understanding how this phenomenon played out at a course and a programme level. At the time, I used the reading lists. This was the only data available to me.

I was looking at the authors and not the designers. I can see now that in terms of diversity, those reading lists were even worse than the collection.

Interestingly, when I talked about this to staff in the department, I was dismissed. Apparently, it was irrelevant because ‘these aren’t the references we actually use’ as educators. Curiously, this was said with no acknowledgment that the reading lists are written by the course staff. I was told that it’s the references given in briefs, lectures, tutorials and presentations that are considered to be the ‘real’ references of graphic design education.

The pale, male tip of the academic iceberg

The problem is that this layer of references is virtually invisible. It is certainly very difficult to track down or interrogate. What we reference in the studio, in tutorials lecture theatres is just as capable of maintaining patriarchy and racism as what we include in our the Library collections. Arguably, more so. As the joke goes… the students don’t actually read the reading list.

The important work of libraries clearly needs to continue and I understand that we the staff, need to play a more active part in it. However, I’ve also come recognise the limitations of this work. Particularly when I begin to consider my own references. For all my thinking about this, when I go back through my own lectures and workshops this year, I find a distinctly Eurocentric list of references. Arguably more women than most tutors, consciously so, but still overwhelmingly white.

The most significant insight for me is that in design collections, the authors will not always be the designers. So, we might succeed in building the most diverse collection of authors in the world. If those authors are all writing about the same old white men of modernism, what have we really achieved?

This is not good enough.

References

Ahmed, S, & Ahmed, A. (2012) On Being Included : Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Duke University Press p45

Kvasny, L (2009) ‘Social Reproduction and Its Applicability for Community Informatics’, Learning in Communities, Human-Computer Interaction Series. ISBN 978-1-84800-331-6. Springer London, 2009, pp. 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84800-332-3_8